|

Mi Piel by: Val Vera The skin I'm in. The brown & disabled skin I'm in. The skin you say is derived from sin. The skin that says I don't fit in. The skin I'm in won't let me in. Your abled world so ivory within. The skin that's rejected again and again. "Hey you Rican" "That chair can't get in" The skin I'm in, a gift from Him? My cross to bear, my sink or swim? The skin that fits my soulful whim. Embraces me until I give in. The skin I'm in, I love this skin. The brown & disabled skin I'm in. Val Vera

Freelance Writer Disability Rights Advocate Denton, TX

2 Comments

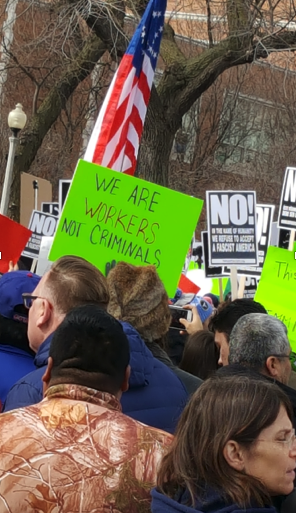

Disability Through Trauma (Reflections on Charlottesville) By: Katherine Perez (Originally posted on Katherine's FB page on August 14, 2017) Disability does not have a race, class, gender, age, religion, nor political affiliation. People are born into our world, while others enter later in life through illness, accident, disaster, or war. Today, I reflect on those who acquire disability because of trauma and violence fueled by hatred. Specifically, a hatred that comes from a system of white supremacy that continues to assault the bodies and minds of our non-white communities (including our Jewish siblings). This entry into the disability world is a site of pain, anger, and sadness. As someone who is proud to be both Disabled and Chicana, I don't shy away from this reality. This reality brings many of my Black and Brown hermanxs into my tangled identity. When hatred leaves scars on one's body and mind, it is hard to derive dignity and pride from those scars. In my work with the National Coalition for Latinxs with Disabilities (CNLD), I often engage in conversations about how centering people of color in the Disability Rights Movement will necessarily shift the definition of Disability. In particular, I've had several important discussions with my mentor Jyoti Nanda, an attorney and academic who is writing about the Compton School cases in which a judge ruled that children who experience trauma in poor neighborhoods could meet the legal definition of disability. I also have discussed, strategized, and taken action with CNLD in protest of the inhumane conditions in immigration detention centers that traumatize and inflict bodily harm on our hermanxs. Through it all, I continue to realize how complex disability is. Today, I condemn the white supremacists, neo-nazis and racists who have left serious physical and emotional wounds on those who protested against them. I join the racial justice community in calling out the structures of oppression that impact our bodies and minds. I am also filled with hope that the disability community has also publicly denounced the violent, racially-motivated destruction that took place in Charlottesville. Although the irony can feel unsettling, it doesn't have to be contradictory. I believe in a strong, cohesive disability community that fights against the racial injustice that perpetrates trauma on our bodies and minds, while also fighting for the right to feel pride to exist in these bodies and minds. For those who enter the disability community because of trauma and violence, know that those of us who are Disabled recognize your pain, anger, and sadness. But also know that your scars represent your resilience in the face of bigotry. You are not less for your altered bodies and minds. You have a community that is ready to embrace you and show you that life with these bodies and minds is worth living and loving. And when you are ready, we need you in the disability community as someone with multiple oppressed identities to help push forward a more inclusive disability rights agenda that includes the fight against racism. In solidarity, Katherine Perez #Charlottesville #Intersectionality #Disability #DisabledLatinx Citations: http://www.npr.org/…/ruling-in-compton-schools-case-trauma-… https://www.facebook.com/events/1793395224064170/ https://dredf.org/2017/08/13/solidarity-racism-hate-bigotry/ Coalición Nacional para Latinxs con Discapacidades  About Persons with Disabilities After the Hurricane Maria Impacted Puerto Rico Yessica M. Guardiola Marrero As many know, Puerto Ricans and other residents in Borinquen are living difficult days of the aftermath of hurricanes Irma and María. Unfortunately, the situation has impacted negatively the life, health and equitable access to the services needed by many people, including persons of all ages with visible and invisible disabilities of all kinds. Many people lost their houses, many others still have no potable water or electricity in their homes. Communication and transportation have been compromised, thus causing logistical issues that have significantly slowed down the island’s efforts to bounce back from the hit, and even left some helpless. The PR and Federal Governments have announced that several regional centers will be established for distribution of water and food. The lines to buy and access food, water, fuel, ice, among other basic things, are very long, more than a week after the event. Official or confirmed information is limited and hard to access. Even though, we read very alarming news, such as that about 200 people have died from lack of oxygen, and in many cases, others from the lack of electricity in the emergency rooms. The Movement to Achieve Independent Living (MAVI by its Spanish acronym), a private, non-profit organization that have been an independent living center for youth and adults with disabilities for 28 years in Puerto Rico, is conducting a study of the needs of individuals with disabilities that remain in shelters. In collaboration with the Northeast ADA Center (NEADA), the National Coalition for Latinxs with Disabilities (NCLD), as well as all entities and volunteers who want to join, will serve as a link so that these people with disabilities can access the corresponding resources to support them. To join this initiative, send a message to: [email protected]. In addition, a young Puerto Rican has created a free digital app that works without having to be connected to the Internet, through which existing needs in any part of the Puerto Rican archipelago can be documented and aid resources directly coordinated, for more information visit: www.conectarecursos.com. Likewise, many other initiatives have spontaneously emerged to support those most in need in this situation. While it is true that times like these seem to be too long, our resilience and will are greater, eventually the sun will rise and peace will come with an improved Puerto Rico. We’ll Overcome This! Yessica M. Guardiola-Marrero Co-Founder of the CNLD Technical Assistance Specialist for MAVI-NEADA in PR [email protected]  Acerca de las Personas con Discapacidades Después del Impacto del Huracán María en PR Yessica M. Guardiola Marrero Como muchos saben, los puertorriqueños y otros residentes en Borinquén estamos viviendo días difíciles luego del paso de los huracanes Irma y María. Desafortunadamente, la situación ha repercutido negativamente en la vida, la salud y el acceso equitativo a los servicios que necesitan mucha gente, incluyendo personas de todas las edades con discapacidades visibles e invisibles de todo tipo. Muchas personas perdieron sus casas, muchos otros todavía no tenemos agua potable o electricidad en nuestros hogares. Las telecomunicaciones y la transportación se han afectado grandemente, causando problemas logísticos que han limitado los esfuerzos locales para recuperarse del impacto, e incluso algunos han quedado incomunicados para pedir ayuda. El Gobierno de PR y el Federal han anunciado que se establecerán varios centros regionales para distribución de agua y víveres. Las filas para comprar y acceder a alimentos, agua, combustible, hielo, entre otras cosas básicas son muy largas, todavía más de una semana después. La información oficial o confirmada es limitada y de difícil acceso. Aun así, se han publicado noticias muy alarmantes, como que unas 200 personas han muerto por falta de oxígeno en muchos casos y en otras por la falta de electricidad en las salas de emergencia. El Movimiento para el Alcance de Vida Independiente (MAVI), una organización privada sin fines de lucro que ha sido un centro de vida independiente para jóvenes y adultos con impedimentos por 28 años en Puerto Rico, está realizando un estudio de las necesidades de los individuos con discapacidades que permanecen en refugios. En colaboración con el Centro de ADA del Noreste (NEADA), la Coalición Nacional para Latinxs con Discapacidades (CNLD), así como las entidades y voluntarios que se quieran unir, servirá de enlace para que estas personas con discapacidades puedan acceder a los recursos correspondientes que necesitan para apoyarles. Para unirse a esta iniciativa, envíe un mensaje a: [email protected]. Además, un joven puertorriqueño ha creado una aplicación digital gratuita que no necesita estar conectada a Internet para usarse, a través de la cual se pueden documentar necesidades existentes en cualquier parte del archipiélago puertorriqueño y coordinarse los recursos de ayuda directamente. Para más información visite: www.conectarecursos.com. Así mismo, han surgido espontáneamente muchas otras iniciativas para apoyar a los más necesitados en esta situación. Si bien es cierto que momentos como estos parecen demasiado prolongados, nuestra resiliencia y voluntad son mayores, eventualmente el sol saldrá y la paz vendrá con un Puerto Rico mejorado. ¡Venceremos! Yessica M. Guardiola-Marrero Co-fundador de la CNLD Especialista en Asistencia Técnica para MAVI-NEADA en PR [email protected] (transcript) COLORBLIND: MEET YOU AT THE CORNER OF INTERSECTIONALITY - A CHAT WITH KATHERINE PEREZ8/10/2017  Thank you, Chakir Underdown, for having me on your podcast. Like I said at the end--you can't get rid of me now! Looking forward to future collaborations especially thinking more about accessibility in law schools for people with psychiatric disabilities. I feel like my answer to your question was inadequate. While I wouldn't urge anyone to disclose in what could be a hostile environment, I would say to law students with psychiatric disabilities that you are not alone! That you are enough. To let go of the rat race for unattainable perfection that law school embodies. What the legal system really needs are people like you to be your authentic selves & to push the boundaries of inclusion! Sí se puede! 🔥 -Katherine (Transcript) COLORBLIND: MEET YOU AT THE CORNER OF INTERSECTIONALITY - A CHAT WITH KATHERINE PEREZ August 6, 2017 Chakir Underwood: Good evening to all of our listeners, you are on with Kinky Summer and I am here with Katherine Perez. How are you? Katherine Perez: Hello! I'm great! How are you doing? Chakir: I'm well. Katherine is one of our AAPD Paul G. Hearne Award winners and you won along with Ola. Can you tell me what you did to win the award? Katherine: Sure. So, earlier this year, I was incredibly honored to attend the American Association of People with Disabilities Annual Gala and to receive the Paul G. Hearne Leadership Award, which they honor for emerging leaders in the Disability Rights Movement. So, I guess I'm an "emerging leader" in the Disability Rights Movement! And, like I've told you before, I felt when I got it, it was so pre-mature, because I had just started, I was just six months in to the co-founding of the National Coalition for Latinxs with Disabilities. Well, and also a lifetime of dedication to people with disabilities. But, just six months into this organization. I was not well-known within this disability rights community. And, I remember entering the gala--it was so beautiful--all the leaders within the rights movement. Like 500 people, everyone dressed up, people like Judy Heumann were there! So, I walk in and I'm just a nobody. And, then they present the award, and it was so beautiful and so honoring the way they did it. And then, I go up. I give my speech. I think I cried through the whole speech because I was just so--it was an incredible moment for me. And, when I came down from the podium from the speech, people basically formed a line in front of me. I went from being nobody in the room to now everyone knew who I was and knew about the National Coalition for Latinxs with Disabilities. I networked that day, and the networking hasn't stopped. So, even though I felt like it was pre-mature, because we hadn't done that much work yet, the award was a motivating factor for me to keep going. And, since then, I feel like every week now, I have been connecting with different people in the rights movement and creating collaborations and coalitions with other people. So, now we ourselves are becoming a powerhouse, the coalition, and it's doing really good things. Chakir: Can you explain to me what is the Coalition? Katherine: Sure. I am one of the co-founders, but one of many of just phenomenal people. I gathered together people within my realm. As you know, I'm a law school graduate and currently a PhD candidate, so a lot of our co-founders are either in academia, are attorneys, are directors of programs, they themselves have started non-profits. I would say that 90% of us--we have maybe like one ally--but most of us identify as Disabled Latinxs. I myself identify as a Disabled Latina. And, we're very proud of that. It's both lead by and for this identity group. And, essentially what we have done is we have all found each other! We are a national coalition. We have people from Northern California all the way down to Florida and Puerto Rico, New York, Chicago, people in the South. And, essentially, these Disabled Latinxs who have been working within our community have sort of felt isolated in the work that they are doing. They are either in a Latinx organization or a disability organization, or they have started their own, and they feel like they are in their own silo working on the project at the intersection of disability and Latinidad. And so we have all just basically found each other--all leaders in our communities. It's like someone said at our second conference, when we finally met each other face to face, that it felt like coming home and we didn't even realize that we were away from home this long. So, really the first thing that the coalition does is it has brought together all these incredible leaders in the Disabled Latinx Movement, to support each other and build off the synergy, and to spread what we now call our "Disabled Latinx Movement." The second part is reaching out to our community. We all have similar experiences and similar goal of united the disability community and the Latinx community. We all have the same experience of people in the Latinx community not doing enough outreach to people with disabilities, and then in the disability community, there is always more call for diversity, more diverse leadership, and more people to identify with the cause. So, we're there on the grassroots level trying to get those who have disabilities but don't really know about the Disability Rights Movement, or don't identify as Disabled, don't really know about their rights, to join the movement. We are an identity org. We obviously take political stances. So, we get more people involved in disability rights and disability justice. Chakir: That's amazing! As you look at yourself as someone who has intersecting identity groups to which you belong, how have you been able to navigate that throughout your life, as a woman, as a Latina woman, I know you're under "woman of color", and you're disabled as well. How does that all flow together for you as you were growing up? Was something pushed to the forefront more than others? Katherine: Yeah. Yeah! I love the way you just framed that right now. How did that flow together? And, it didn't. I think my identity felt really fractured. And, up until recently, like I said, up until recently, we just had our second annual conference at the Ed Roberts Center in Berkeley, California, just a couple of months ago, and meeting up with other Disabled Latinxs really was the first time I found my people who had these intersecting identities who got it. Otherwise, I felt like I was either existing in a disability space or I was existing in a Latinx space, right? And, both spaces didn't understand my other identity. So, my own identity formation has been an evolution. I have mental disability. So, when I was younger, I thought of it more as a diagnosis, it was a health thing, something I took meds for and went to therapy for. If I could find a cure for it, that would be great. It wasn't about being part of the community, or being part of the culture, or identifying as Disabled even. I identified more as being "mentally ill" and now I say mental disability because I identify with a disability community. My sister has intellectual disability, and she's a year younger than me. She was the one who got me into disability justice because she was more... what we have is like I have is more the "non-apparent" disability and she has the more "apparent" disability, so she was in the disability community from a very young age. So, my sense of disability justice was really raised through her. So, again with this idea of the evolution of identity, my disability identity really wasn't firm until my adulthood years, recently, when I felt like I could really claim it. And, meeting these people who are Disabled Latinxs was really the first time where I've felt like a community who really understands what it was like to live within the intersection of Latinidad and disability. Chakir: Well, I definitely understand that! So, you mention that you are a law school graduate, and now you're a PhD candidate. I mean law school is tough, let's just put that out there! Katherine: (Laughter). Chakir: (Laughter). Tough is one word to describe law school. Katherine: (Laughter). You know that! Chakir: Yes! So, what propelled you to just say "you know what? Let me just go get this PhD, too"? Katherine: Right. (Laughter.) So ridiculous. But, you know if I were to go back I would do it again. I'm having the time of my life. When I went into law school, I wanted to be a disability rights attorney. And, I still do. And, I probably will when I graduate next year, I will maybe practice for a few years before I go into academia or policy. But, when I went to UCLA Law, in the three years that I was there, they never offered a Disability Law course. I started a Disability Law Society at UCLA, and we held a conference, and that's when I sort of did the research on who are the critical disability legal scholars out there. And, there's very few. Mighty, but few! And, I was in the Critical Race Studies program at UCLA Law, with some of the most foremost scholars like Kimberle Crenshaw, Devon Carbado, Jyoti Nanda, etcetera. And, I just loved what they were doing critiquing the law through a Critical Race Studies perspective, and I thought "we need to do this in disability." Not only do I want to practice within disability rights law, I want to critique it, and I want to push the boundaries of it, and I want to help it evolve into better policy. And, because I didn't have that foundation... again, I never even took a disability law course. I looked up programs for what that would be like. And, I found this program at UIC, which is where I am at now. I think it's the only PhD program in Disability Studies in the nation. It's a phenomenal program, and I am starting my fifth year there. And, I am so happy that I am. And, now I am actually doing the work of merging Critical Disability Studies perspectives into the law, and then hopefully will be pushing boundaries as a Critical Disability Legal Scholar. Chakir: That's quite amazing. I applaud you for taking on another academic school. Katherine: (Laughter). Chakir: I mean seriously, it's a level of discipline that many people would shy away from in a heart-beat. Katherine: Yes. Chakir: I mean the amount of reading that you do in law school, you know it's just like "I'm done!" I remember, 2L summer, I finished, and I am like "I don't even want to read a magazine." Now you're sitting here saying "I'm going to dive into a dissertation!" Katherine: Exactly. Yea, I think what I told you before when we talked about this, I think I probably have the same level of work, maybe even more, but at least now it's all focused on my dissertation, and what I love to read and what I love to write about. So, you know, I don't have a contract class that I have to worry about! (Laughter.) That I'm not necessarily interested in. So, you know, even though it's a lot of work, it's my passion. I'm living my passion. So, I'm incredibly lucky. Chakir: That's wonderful. So, what is your ultimate goal when you finish this PhD, you know, you have this coalition, you have your credentials... what is next for Katherine? Katherine: So, like I said, the AAPD Paul G. Hearne Award thrust me into the leadership of the Disability Rights Movement. And, for me the future of the disability rights movement is intersectional, necessarily intersectional. So, whatever I do, I feel committed as a disability advocate and activist, not only as a scholar but as an activist. So, now we're about a year into our coalition, and we're now applying for our 501(c)(3) status. So, hopefully when I graduate, by then, we will have that status, and I will take on a big role as either the ED or a board of director position on the coalition. And, it will just continue grow, and I have so many ideas about how we can expand it. And also, like I said, because I'm going into 7 or 8 years in academia, I think I'm probably going to be ready to practice law or do something in the policy realm just to get out of the ivory tower and my head out of the books, and sort of fight the fight with all these incredible disability rights leaders who I have made connections with over the years. I'll still be part of the community, just fighting from a different office! Chakir: Yeah, that's totally fine. It's a more natural progression than many people think. You can shift from academia and come out swinging. And, also the level of education and breadth of knowledge that you have is really powerful especially if you want to get into policy work, so that's phenomenal. Katherine: Thank you. Chakir: Oh, you're welcome! Just give me a teensy bit, you know you told me that you deal with mental disability. And, so can you tell me, especially as a woman of color, how does that affect your day-to-day? I can imagine with all you do, you probably have had people walk up to you and say, "oh my gosh, how do you do it? how do find time?" Katherine: (Laughter). Chakir: "How do you blanace it?" Trust me--I've heard all of it! Katherine: Yup. You know! Chakir: So, how do you deal with it? Katherine: Well, yea. I think you and I have, again, have talked about activist fatigue. It's kind of ironic that I'm in this line of work because some of my body/mind experiences with mental disability is that I get really fatigued, you know, coming out. Intentionally. And, I intentionally put myself out there that I have mental disability when I do podcasts like this, when I'm writing an article, when I'm speaking in front of a class, or giving a lecture, etcetera. So, you know, I still feel the stigma. The stigma is very real, right? So, even just coming out continually as an activist can just take a toll on me. And, just, yeah, I think, people with mental disabilities, when you think about accommodations, I think a lot of the accommodations that we need have to do with time that just aren't really conducive to this "go-go-go", capitalist structure that we have. There is a lot of burn-out, and we need time to process, and deal with emotions and over-stimulation, etcetera. And, like I was telling you, and we were talking about this before. I feel like I have been able to deal with it really well because I'm in this bubble right now. As I keep saying, I met this community, I found this home of other Disabled Latinxs, so I have an incredible group of colleagues who are now some of my dearest friends, who get it! So, when I need to take a break, when I need to check out, you know...if I need to have strange hours, work at 4 in the morning, because that's when I'm being most productive, you know, these people get it! They are there to support me, and they are not there to judge. And, I like to feel like I'm there for them as well, in that way. Chakir: So, before the coalition came together, did you have those points of solidarity as well, were there other coping strategies that you had employed, especially during law school? Katherine: No, you know what's interesting? I did have a lot of methods of coping. Because, you know, I have had mental disability since I was a child, from my earliest memories. So, you get really good at coping. But, you also get really good at passing. So, during law school, you know, again this notion of time, and being flexible with time, and being accommodating with time, is just not something that happens in law school at all. It's go-go-go, it's competitive, it's very structured. So, you know, I kind of just grit and didn't have this home of Disabled Latinxs that I have now. You just go through it, and your body takes a toll and your mind takes a toll. Law school has a ... not just law school, many structures... but, law school has a far way to go before it can be accommodating to people with disabilities not just mental disabilities. You know, you kind of just grit and bear it. So, now, again, coming out as having mental disability and finding a home and doing the work within the rights community, I think I've been able to be my more authentic self and be more productive. You know, all these wonderful people that I know who are Disabled Latinxs or just people with disabilities are incredibly brilliant, and have great ideas, and can add to the workplace, etcetera, if we could just think of creative ways to accommodate them to be part of these systems, to be part of the workplace. We have so much to bring. You know, I think that outside of this bubble that I'm in, we have a lot of work to do. Chakir: I definitely agree with you. And, there's so much that can be said for those who help you to feel empowered and that you are able to embody all of yourself, because when that happens, you can bring all of yourself to your work product. Katherine: Exactly! Chakir: It is a phenomenal change. Is there anything you might be able to say as words of advice for law students who are facing psychiatric disabilities and what we can do? Should we do more to come out publicly? Are there things that we can try to demand? Or, working more with the faculty and staff? Anything like that? Katherine: For law students? Yea, I'm kind of weary about... You know, here I am, I'm very out and proud about having a mental disability. But, I said, I'm very conscious that the stigma is real, and that the consequences of claiming a mental disability are very real outside of this bubble that I keep talking about. You know, and within academia it's still stigmatized. So, it's a really tricky question, Chakir! You know, in law school, I wasn't.. I didn't really come out to my professors like in the way I do now. And, I would never push upon someone who doesn't feel comfortable to come out, to come out, because it can be a very unsafe environment for people to do so. So, for those who are coming out, it's really great, and they are doing the groundwork. But, I think, we really need, the activist really need to push to transform law school to be a more accommodating place. And, you know, I wouldn't make a broad announcement that all law students with psychiatric disabilities should be out and free, because that could be dangerous for a lot of people. Chakir: Definitely. Well, we hope that the stigma especially can be broken down and that can help to enrich the law school environment, and other, of course, practices, academia, other degree tracks as well, from the professional, to the graduate, undergraduate, certificate programs, what have you... Katherine: And, yea, you know, people are doing lots of great things to break down the stigma and barriers. You were telling me the other day that on the last American Bar Association magazine, or whatever it was, was talking about alcoholism. Which was like, it's great that they are talking about it (laughter), but it's like hello!, we've had this problem within our profession for so long, so we're finally just talking about it. Chakir: Oh yeah. Katherine: I think of people like Dior Vargas. She's someone who is in our coalition, she's one of the co-founders. She has this really phenomenal project around breaking the stigma around mental disability, mental illness, so she's just doing phenomenal work. So, you know, people are doing a lot of great things, and I think things are changing, and we have a lot of work left to do, but I am hopeful about the future. Chakir: Thank you. Thank you, I do appreciate that. Well, I think my final question just to close out with all of this. We have discussed a lot of topics all interrelated here. What would be one thing that you would be able to change, right now, you would be able to change with a snap of a finger, what would it be? Katherine: Well, my sister just popped into my head, because she's having a hard time right now. My sister has intellectual disability, and she's an adult right now. I just wish that there were more options for people with intellectual and developmental disabilities as adults. She has like this one program that she gets through Medicaid...right? And so, I guess, if anything... (laughter)... I could just snap and get this healthcare bill off the table completely and figure all that out and save Medicaid. But, to be even more specific is not only have the healthcare that we are fighting for, but to have even more options. Right? So, again I go back to people like my sister, we're fighting for basic Medicaid services, but ultimately what we want are more options, more options... So, just not one program that she goes to one day program where they are walking through malls all day, or whatever they are doing. You know, my sister, just like everyone else, wants to have a job, wants to move out and live on her own, wants to have a family, wants to date. She has all these needs and all these desires that everyone else has. So, if we could create a society, if I could snap my fingers and create a society where it was the standard where we have more options for people with disabilities and not just us fighting for just to save our Medicaid at this point, that's what I would snap my finger and do. Chakir: I think that's beautiful. And, I would hope that in our lifetime that we get to see that society, or at least see tangible indicators of a formation of that society. I think that is a dream that many of us do share. So, thank you so much for your work, your wisdom... for you work, it's amazing, Katherine. Katherine: (Laughter). Oh, thank you! You're so kind. And, to you as well! Chakir: (Laughter). Thank you! I look forward to seeing more of what you're going to bring to the table. I definitely look forward to connecting with your coalition and seeing more of what they are going to do. More conferences! Here's to getting your non-profit certification. And, all the best wishes to you on finishing your PhD. (Music fades in). Katherine: Likewise, and to you in law school. I mean, you can't get rid of me now! You and I are connected, so... Chakir: (Laughter). Katherine: I am excited for our collaborations going forward! Chakir: Thank you so much! So, today we are signing off with Katherine Perez with Kinky Summer. I am Chakir Underground... we will chat soon. (Music stops).  de: Gerardo Salinas ¿Cómo puedes navegar en el internet o puedes escribir en una computadora? Es una pregunta que muchas personas hacen cuando escuchan o miran que una persona invidente está enfrente de una computadora. ¿Es posible que una persona invidente pueda estudiar, hacer tareas, leer y tambien tener un empleo el cual requiere usar una computadora? Dudas, curiosidad sorpresa es la reacción de varias personas. La respuesta es sí, hoy en dia se cuenta con mucha tecnología adaptada la cual permite realizar muchas actividades desde una computadora. Actualmente saber usar la tecnología es fundamental para ser más independientes y lograr metas que nos ayudan a avanzar como comunidad e individualmente. Desde el poder encontrar un mejor empleo, estudiar, hacer compras en línea y mas es lo que nos beneficia una computadora. En el caso de las personas con alguna discapacidad la tecnología es clave y de mucho apoyo ya que nos permite ser más independientes cada dia con nuestras actividades e ocupaciones dentro y fuera de casa. Para una persona invidente usar una computadora es posible gracias a un lector de pantalla llamado JAWS, este sistema permite a la persona invidente navegar por el internet, escribir documentos, leer correos electrónicos, leer libros digitales, hacer compras, asi como usar las redes sociales. El sistema va narrando/describiendo lo que está apareciendo en la pantalla de la computadora asi como la función del teclado que cada tecla que se selecciona el sistema avisa cual tecla se seleccionó para escribir. Es asi como una persona invidente puede estar detrás de una computadora haciendo sus actividades escolares, laborales y personales. Otras herramientas muy importantes que asisten a una persona invidente con sus actividades son las aplicaciones que se pueden bajar a través de los diferentes dispositivos como teléfono celular y tableta. Estas aplicaciones/apps ofrecen varias funciones, desde identificar los colores de la ropa tan solo con tomar una foto a la prenda de ropa la aplicación describe el color. Otra de las aplicaciones asiste con identificar objetos, es decir tomando una foto a un objeto o persona la aplicación es capaz de describir el objeto, articulo o la persona. Asi como tambien se cuenta con otra aplicación la cual ayuda para poder identificar el dinero de la misma forma solo tomando una foto con la cámara del teléfono y la aplicación lee la cantidad. Estas son solo algunas de las muchas apps que se pueden encontrar disponibles y de forma gratis para bajar en los dispositivos. En conclusión, la tecnología adaptada hoy está haciendo una gran diferencia en la vida de muchas personas con alguna discapacidad desde física, emocional y mental. Dependiendo el tipo de discapacidad se puede encontrar y usar alguna aplicación que apoye y asista a la persona con la discapacidad para ser más independiente. Desde poder estudiar, trabajar y entretenimiento. Estas apps nos ayudan a estar conectados con el mundo y estar activos en la sociedad. Esta tecnología es clave en mi diario ya que como persona invidente dependo de esta tecnología adaptada para poder estudiar, trabajar y socializar. Conocer esta tecnología y aprender a usarla puede ser una gran diferencia para lograr y superar más barreras como comunidad Latina con discapacidades.  By: Irad Ulysses Flores On Thursday February 16, 2017 I participated in the Chicago “Day Without Immigrants” boycott/protest that occurred in many major cities across the U.S. The protest was aimed at emphasizing the social and economic contributions that immigrants, documented or not, bring to this country. It was a movement rooted in solidarity between all groups of immigrants affected by the current political climate. The rally held in Union Park was full of predominantly Latinx immigrants and their allies. Mexican, Guatemalan and Honduran flags flew high and proud as speeches giving anímo to our brothers and sisters were given. People brought their children and had them hold up signs like, "We are workers, not criminals". The solidarity across age groups was astounding, but this same solidarity extended beyond the scope of age. There were allies of all ethnicities and backgrounds present, from White Union workers, to “Jewish Voice for Peace”. Also among this diverse crowd were many disabled Latinx elders: using their walkers, canes, and wheelchairs. This rally then moved into a march heading west on Ashland Ave, shutting down the streets lined with businesses that closed down in support of the protest. It was an amazing scene. This was my first ever involvement in a rally or protest, and I can say without a doubt that being a part of the Disability Studies program at the University of Illinois at Chicago, and being a part of CNLD has inspired me. I have always had issues that mattered to me, but I never understood the importance of activist actions like protests and rallies. Through my education I have learned about the Disability Rights Movement, the 504 sit-ins, and the exclusion of people of color from these narratives. My hope is to involve myself and my family in Disability rights issues to make sure the contributions of our people are not blotted out again. Though the general Latinx community stands to be harmed by the beliefs and policies of the current administration, the Disabled Latinx community specifically faces great potential harm. The only way to fight back against systemic injustice is by amplifying our voices. Protests and rallies can accomplish this; and after getting my first taste of activism in February, I am ready to keep fighting for my Disabled Latinx hermanxs.  de: Gerardo Salinas Enriquez ¿Soy normal o anormal? ¿Estoy bien o no estoy bien? Todos los días despierto abro los ojos del corazón y de la mente y me pongo activo con una actitud positiva de luchar por lograr mis metas/sueños de graduarme de la universidad con una carrera, de mantener mi empleo, asi como continuar haciendo mi programa de radio/tv donde detrás de un micrófono puedo presentar información, educación y motivación entrevistando a las personas indicadas en cada área. Sueno y planeo graduarme, conseguir empleo en mi aria de estudios que es Ciencia Política, Estudios Latino Americanos y Estudios de Desarrollo Humano, comprar una casa, formar un hogar y dar lo mejor de mi persona, y disfrutar la vida con alegría, respeto, paciencia, voluntad y mucho amor. Mi dia comienza asistiendo a la universidad a tomar mis clases con la motivación de que pronto me podre graduar. ¿En el camino a la universidad usando la transportación conozco a algunas personas que me preguntan a dónde vas? Yo les contesto buenos días voy a estudiar y a mis clases a la universidad. ¿Las personas me contestan de verdad? Les contesto si soy un hombre con muchas metas y sueños. Me contestan en verdad te admiramos porque tú que no estás bien estas estudiando haces eso y nosotros que estamos bien no hacemos eso. Las personas continúan comentando eres una inspiración porque tú que no estás bien o normal puedes ir a una universidad y tienes alegría y fuerza. ¿Y me quedo callado por unos segundos y les pregunto que es estar bien y no estar bien? Las personas se quedan calladas y dicen bueno pues asi como a ti que te falta algo. Y la plática termina ahí y yo tengo que bajarme porque yo he llegado a mi destino final que es la universidad. Y en mi cabeza se quedan estas palabras “No estás bien, te falta algo, no eres normal,” y entro al salón de clases dispuesto a aprender algo nuevo y convivir con el resto de mis compañeros de clase. ¿Termina mi participación o rutina de clases y me siento junto a la puerta de la universidad a esperar mi transportación y alguna persona se acerca y me dice cómo te llamas? Y les contesto Gerardo y me dice bueno solo quiero decirte que te felicito porque vienes a estudiar a pesar de que no estas bien y un segundo después la persona se retira. Unos minutos después me pongo en marcha en camino rumbo a mi empleo, y después de 15 minutos llego a la organización o centro comunitario que es mi lugar de trabajo. La organización para la cual trabajo ofrece servicios y clases para los adultos y personas en general, desde clases de inglés, computación, nutrición y más. Tambien se ofrece un programa que ayuda a personas con alguna discapacidad física, mental o emocional a encontrar empleo y asistirles para que puedan tener una vida más independiente. Mi ocupación es asistir a las personas con alguna discapacidad a llenar solicitudes de empleo y prepararlos para la posible entrevista de empleo. Tambien estoy encargado de crear conexiones con diferentes organizaciones y crear eventos para informar a la comunidad Latina sobre los servicios en general que el centro ofrece y los servicios para personas con alguna discapacidad, al igual que trabajar con los medios de comunicación. Durante mis horas de trabajo me reúno y tengo citas con personas que supuestamente están bien o normales que buscan algún servicio o tienen preguntas y necesitan hablar conmigo. ¿Cuándo la persona me conoce una de sus primeras preguntas puede ser tu aquí trabajas o como es que puedes trabajar? Yo contesto si aquí trabajo y me encanta mi empleo y el poder ayudar. La persona contesta bueno felicidades hay muchas personas allá afuera que están bien y no son capases de tener un buen empleo asi como tu aquí que tienes tu oficina. En verdad Gerardo muchas felicidades porque tú que no estás bien trabajas y estudias y mucha gente que está bien no hace nada. Termina mi dia de trabajo y antes de llegar a casa voy a los estudios de radio a grabar y presentar mi programa de radio/tv y presentar la información, motivación y educación con nuestro invitado en los estudios. El programa de radio dura una hora y durante esta hora muchas personas mandan saludos, dan las gracias por el tema/información, comentan que les gustó mucho y que es de mucha ayuda. Y otras personas me mandan algún mensaje diciendo felicidades te admiramos porque tú eres un ejemplo, porque a pesar de que no estás bien puedes hacer todo eso de estudiar, trabajar y lo de la radio, y eso que no estas normal o bien, y nosotros que si estamos bien no luchamos por nuestras metas. ¿Les contesto gracias por sus saludos y comentarios y les hago la pregunta que es estar bien y no estar bien? Nadie contesta y mi pregunta se queda sin respuesta. Al final del programa me pongo en marcha a casa después de un largo dia, pero con la satisfacción de hacer lo que me gusta y dar lo mejor de mí. ¿Llego a casa haciéndome esta pregunta que es estar bien y que es no estar bien? Soy un hombre que tiene una discapacidad física, pero que tengo muchas habilidades, inteligencia asi como defectos y limitaciones. ¿Pero que acaso nadie tiene limitaciones? ¿O es que todos tenemos solo virtudes y talentos? Sera que solo Yo Gerardo tengo limitaciones? Sera que las demás personas que se dicen estar bien o normales no tienen dificultades para realizar algunas de sus actividades diarias? ¿Como sociedad podemos decir a alguien tu no estás bien como nosotros? ¿O tu si estás bien y no haces nada por superarte? ¿Que acaso no somos iguales? Diferentes estatus económico y social podemos tener cada persona. ¿Pero mi pregunta y reflexión para todos es que es ser normal o estar bien? ¿Yo estudio, trabajo, presento radio y para una gran parte de la sociedad soy inspiración porque no estoy bien como muchos de ellos y se sorprenden como es que puedo hacer estas actividades? ¿Pregunto las habilidades que yo tengo tambien la tienen los demás? ¿Las limitaciones que yo enfrento tambien las enfrentan los demás en nuestra sociedad? ¿Que acaso no todos contamos con diferentes habilidades, talentos y capacidades para realizar nuestras actividades y lograr nuestras metas? ¿O que acaso no tenemos algunas limitaciones para lograr algunas metas y actividades? ¿Dicen hay personas que están bien y no hacen nada por superarse o lograr sus metas y Yo que no estoy bien las logro? ¿Es voluntad, perseverancia o que es? ¿Donde está la discapacidad? ¿Si yo no estoy bien como parte de la sociedad comenta entonces como es que sigo superándome? Es verdad que no puedo ver con los ojos físicos, pero si tengo mucha visión para lograr mi misión, superación y proyectos. De: Sara María Acevedo y Mónica Vidal Gutiérrez

https://autismoliberacionyorgullo.com/2017/03/06/el-lenguaje-que-nos-define-desorden-espectro-o-diferencia/ Decir es Hacer: En escritos anteriores hicimos hincapié en el impacto socializador del lenguaje como sistema simbólico de intercambio sociocultural y como herramienta comunicativa de uso diario. De una manera o de otra el lenguaje es un agente que ejerce ya que el lenguaje no solo dice sino que hace. Por ejemplo a nivel político, el lenguaje tiene una función tanto práctica como estructural y se activa de acuerdo con ideologías dominantes y normativas sociales. Al desempeñarse en este rol el lenguaje funciona como una herramienta de control social con alcance material, tanto así que tiene el poder de manifestar realidades concretas de acuerdo con políticas sociales de carácter directivo, apelativo, reprimente y excluyente – he aquí un ejemplo sociológico y literario que sirve para ilustrar este fenómeno: En el escrito de George Lakoff y Mark Johnson (1980) “Metaphors We Live By” que traduce al Español Metáforas de la vida cotidiana, vemos como el lenguaje funciona más allá del plano simbólico mediante el uso de metáforas que evocan realidades concretas. En este sentido los autores describen con ejemplos comunes el efecto estructurante de las metáforas cotidianas en el contexto lingüístico de la argumentación, la apelación, y la convicción. Tanto en los párrafos introductorios como en la conclusión del escrito, Lakoff y Johnson aseguran que el lenguaje es ‘estructurante’ y que su uso específico y contextual refleja el devenir de la vida diaria, incluyendo las convenciones culturales, las relaciones sociales y la percepción conceptual e identitaria. Nuestro interés en este texto que además de ser estéticamente valioso ofrece un estudio sociolingüístico bastante interesante y acertado, proviene sobretodo de su énfasis en la idea de que el lenguaje es un agente activo y no pasivo; en otras palabras el lenguaje no solo dice algo sino que hace algo al decirlo. Lo que revela el escrito de Lakoff y Johnson es que las metáforas, sobre todo aquellas que debido a su uso cotidiano pasan desapercibidas, tienen aún más poder apelativo que las metáforas de tipo literario que se usan de manera más deliberada en textos poéticos por ejemplo. Lo que también esclarece este análisis es que al intercambiar información en contextos cotidianos los interlocutores no somos del todo conscientes de los efectos que estos intercambios producen más allá del acto comunicativo. Pero la realidad es que las metáforas de uso cotidiano tienen mucho que ver con la creación de relaciones sociales, sistemas culturales y estructuras políticas dicótomas: esto es, incluyentes o excluyentes; y aunque la meta aquí no es ofrecer un análisis estilístico o político completo de este texto, es importante mencionar que escritos como éste ayudan a ilustrar más claramente las funciones del lenguaje a las que nos referimos al insistir en que el discurso no solo dice sino que también hace. ¿Qué hace el lenguaje al esconder formas de opresión social bajo la máscara de lo cotidiano? Desde el punto de vista del modelo social[1], es imposible trazar la trayectoria histórica y genealógica de la discapacidad independientemente de los procesos sociolingüísticos que la circunscriben y aunque debido a la visibilidad y la fuerza política que han tenido los movimientos sociales que defienden los derechos de las personas discapacitadas en el globo norte (incluyendo Estados Unidos y Europa) la mayoría de ejemplos emergen de la literatura anglosajona, éste fenómeno es observable a nivel global. En Cultural Locations of Disability que traduce al español “Locaciones Culturales de La Discapacidad”, Snyder y Mitchell (2006) realizan un estudio multifacético del movimiento eugenista en los Estados Unidos, al seno del cual incorporan uno de los ejemplos más destacados en la historia de la discapacidad: El nacimiento del Régimen Diagnóstico (Diagnostic Regime) a principios del siglo 20. Según Snyder y Mitchell la creación de este sistema socio-métrico basado primordialmente en el diseño de descriptores patológicos y etiquetas clínicas tenía como meta el desarrollo de taxonomías exactas y “puramente científicas,” mediante las cuales categorizar ‘desordenes’, ‘condiciones’ y ‘disfunciones’ físicas y mentales de manera sistemática. El trabajo de Snyder y Mitchell es fundamental en que busca situar en esta cuna ‘científica’ la producción sociopolítica de los cuerpos discapacitados y por consiguiente de la experiencia global de la discapacidad tras la imagen de todo aquello que es defectuoso, aberrante, monstruoso y criminal. Pero detrás de todo proyecto ‘puramente científico’ yacen factores sociales y culturales que pesan más que cualquier ‘realidad factual o demostrable’; de hecho, es el peso político del canon occidental del conocimiento – que se consolida sobre los pilares de la supremacía blanca y la xenofobia – lo que ha hecho que campañas racistas, etnofóbicas y capacitistas como el eugenismo prosperen bajo el auspicio de lo ‘puramente científico’. El impulso de capturar momentos específicos de la historia de la discapacidad en escritos contemporáneos como éste tiene un propósito doble. Por un lado se busca iluminar la trayectoria de sistemas ideológicos y de políticas sociales basadas en el odio, el miedo y el prejuicio, por otro se busca excavar y centralizar los orígenes históricos del estigma social y su conexión con las creencias y actos opresivos en el contexto actual. Más importante aún es la apelación a la memoria colectiva y la interrupción de ideologías y procesos modernos basados en el culto de la ‘civilización’ occidental, el progreso, la productividad y la destrucción virtual del pasado. De entre todos los métodos posibles de excavación genealógica con respecto a la historia de la discapacidad nos inclinamos aquí por el marco sociolingüístico. Discapacidad y Metáfora: Tradicionalmente la representación lingüístico-cultural de la discapacidad es bastante única y peculiar. Por un lado es común encontrar abundantes referentes a la discapacidad en la literatura clásica, en los textos infantiles y en las fábulas, en escritos antropológicos y en el folclore popular – pero nunca en libros de historia o geografía. Paradójicamente es casi imposible encontrar referencias o ejemplos de personas discapacitadas con nombre propio participando en actividades de la vida diaria o en contextos sociales cotidianos. ¿No es curioso que la discapacidad aparezca siempre de manera espectral en la consciencia colectiva pero nunca en contextos concretos? Es como si la discapacidad fuera una experiencia inmaterial. La realidad es que un gran porcentaje de la población mundial vive con discapacidad/es y se ve forzada a asumir la ignorancia de un colectivo que parece no tener conflictos éticos al consumir historias reconfortantes sobre la discapacidad sin saber absolutamente nada de la realidad de la vida diaria de los millones de personas discapacitadas que viven en sus comunidades. Es cierto que a través de la historia la discapacidad ha adquirido gran visibilidad a nivel simbólico, sobre todo a través del uso de metáforas que buscan representar experiencias colectivas que no guardan relación alguna con las experiencias materiales de las personas discapacitadas. En Narrativa Prostética (Narrative Prosthesis) Snyder y Mitchell (2000) escriben muy claramente que la discapacidad – las caricaturas de los cuerpos discapacitados – ha servido comúnmente para denotar experiencias de catástrofe individual y colectiva de los no-discapacitados a través de imágenes de cuerpos mutilados o decrépitos, enfermos, mutantes o deformes. Esto tiene mucho que ver con que las experiencias propias de las personas discapacitadas en occidente (y en otras partes del mundo, por supuesto) permanecieron encerradas por ley en hospitales, casas de salud mental, asilos y cárceles hasta hace menos de un siglo. Pero en esta dinámica de poder existen dos fuerzas: La que oprime y la que resiste. La resistencia es un fenómeno que por su calidad subversiva y marginal tiene poca presencia en los anales de la historia – después de todo las victorias las narran los que tienen acceso irrestringido a los archivos lingüísticos del poder institucional. Lo que ha hecho que aquellos que disputan el poder opresivo desde los centros locales y públicos figuren como una fuente inagotable de explotación y consumo histórico. Pero la resistencia existe a todos los niveles y en todos los aspectos de la vida diaria. Los varios colectivos de personas discapacitadas se han venido consolidando en protesta pública y de manera orgánica alrededor de metas políticas comunes. Una de estas metas tiene que ver con la invalidación y algunas veces con la reclamación de etiquetas clínicas bajo las que muchas personas murieron en agonía o fueron torturadas y sobrevivieron tratos y condiciones inhumanas. Espectros históricos y actuales: A veces parece que la presencia espectral de la discapacidad aun nos acecha; a menudo se oye una polifonía de voces indistinguibles entre las que nosotros no estamos, que discuten sobre cómo llamarnos, clasificarnos, escondernos, borrarnos, cambiarnos – es un empeño indescifrable en ‘curar’ lo que no ven. ¿Será que el no verse reflejados en nosotros les causa desasosiego y les invade entonces un deseo de organizar? Tanto desorden no es bueno para la productividad…y es curioso que al gustarles tanto la organización y tan poquito el desorden hayan creado todo un régimen diagnóstico en 5 ediciones que sólo habla de eso: Desórdenes. ‘Desorden de Espectro Autista’ es una de los vocablos favoritos de los últimos tiempos; los médicos lo han popularizado y padres de autistas e incluso muchos autistas lo han recibido como alternativa al concepto de desorden – pero solo fuera del consultorio. Nótese que respetamos sin duda el derecho de cada autista, no de sus padres ni de su terapeuta, a elegir el lenguaje que más le satisfaga. Dicho esto, la verdad es que desde el punto de vista del modelo social de la discapacidad, aceptar el concepto de espectro como un agente liberador es limitante. No queremos dejar de reconocer que hay autistas que han resignificado el concepto de espectro adaptándolo con mayor fidelidad a nuestra realidad y aun así el concepto de espectro sigue siendo estereotipante, jerarquizante y lineal ya que se basa en nuevas clasificaciones de acuerdo a la funcionalidad percibida desde un punto de vista no-autista: Bajo, medio y alto funcionamiento continúan siendo los puntos de partida o llegada del espectro. Si bien hay autistas que se identifican como “en el espectro” para decir que no están de acuerdo en clasificarse en alto, medio, bajo, sino en algún lugar incluso variable dentro del espectro no lineal, otras veces ese “estoy en el espectro” se convierte en sinónimo de “autista pero no tanto”, una manera de enajenarse de la versión estereotipada y trágica del autismo que se promueve desde el paradigma de la caridad. Una de nuestras mayores preocupaciones es que la jerarquización del autismo acusa un gran peligro para el presente y el futuro de la colectivización interna y colaboración multilateral con otros movimientos que buscan la justicia y el cambio social. No hay que olvidar que los sistemas jerárquicos son astutos y el adoptarlos cumple con el propósito de las agendas neoliberales que se empeñan en dividirnos. Nos preocupa también la idea de que para separarnos del concepto de desorden nos veamos obligados a enemistarnos entre nosotros. Esta es una táctica del aparato neoliberal que autores como Jasbir Puar (2007) han llamado “excepcionalismo” y que consiste en conceder privilegios o estatus social temporal a aquellas facciones de un movimiento social que al verse presionadas sucumben a facilitar estas divisiones. Un famoso ejemplo es el que Mattilda Berstein Sycamore (2012) identifica en Estados Unidos entre el movimiento Gay y el movimiento Queer – como lo expresa en su Libro ¿Porque Le tienen tanto miedo los maricas a los maricas? (Why are Faggots so Afraid of Faggots) algunas facciones del movimiento Gay se han visto presionadas a adoptar formas de vida que se distancian políticamente de sus contrapartes Queer. Entre otras cosas al participar en la lucha por la igualdad al matrimonio, a la adopción, al gusto por la vida Gay en parejas monógamas, el estilo de vida de clase media y la repulsión por los actos sexuales en público. De manera similar las actitudes jerarquizantes perpetúan mitos del autismo y así la división en ‘castas’ de funcionamiento que no son objetivas ni útiles y que tampoco promueven la auto-determinación. Al comunicarnos con otros autistas percibimos la similitud de nuestras experiencias y de nuestras metas comunes en temas de acceso y de aceptación social. Sería una gran pérdida privarnos o excluir a otros de la experiencia colectiva de una comunidad tan enriquecedora como lo es la nuestra. En conclusión, más allá de ser complacientes con la idea de que lenguaje es un elemento inofensivo que no tiene el poder de separarnos, debemos convenir y organizarnos, unirnos, apoyarnos y ampliar nuestras voces. Hoy por hoy el identificarnos como autistas (¡punto!) es lo más incluyente, además preferimos incomodar a quienes promueven los mitos del paradigma médico, las asociaciones asistencialistas y vendedores de tratamientos; incluso a muchos autistas que no se quieren identificar con “los otros”. En vez de validar distinciones, que pueden ser más ‘convenientes’ a nivel individual, lo que es justo es promover la idea de un autismo en el que todos tengamos el derecho equitativo a una vida plena y digna sin etiquetas funcionales o jerarquías. [1] Ver entradas anteriores Lista de Referencias Lakoff, George, and Mark Johnson. Metaphors we live by. University of Chicago press, 2008. Mitchell, David T., and Snyder, Sharon L. 2000. Narrative prosthesis: Disability and the dependencies of discourse.University of Michigan Press. Puar, Jasbir K. 2007. Terrorist assemblages: Homonationalism in queer times.Duke University Press. Snyder, Sharon L., and David T. Mitchell. 2007. Cultural locations of disability. Sycamore, Mattilda B. 2012. Why Are Faggots So Afraid of Faggots?: Flaming Challenges to Masculinity, Objectification, and the Desire to Conform.AK Press. [Descripción de la imagen: Fondo negro con el texto en el lado izquierdo “El lenguaje que nos define:” en color morado y bajo este texto “Desorden, espectro o diferencia. ” en color verde limón. Al lado derecho hay una imagen de una estrella de seis puntas color naranja, rodeada con con hexágono verde, de cuyo interior salen rayos morados. En el interior de la estrella hay una flor de 6 pétalos de contorno blanco en cuyo interior hay un hexágono color naranja. Centrado, en la parte inferior está el texto “Autismo, Liberación y Orgullo”]  Katherine in the snow with her fur babies. Katherine in the snow with her fur babies. By: Katherine Perez I am honored to be acknowledged for my leadership. I represent a little girl who grew up feeling a little weird and always out of place. My emotions ran higher than Mariah Carey's whistle register and deeper than a Barry White song. My routines were sacred. I would die if I didn't do them. I know what it's like to make the agonizing decision to keep living. I also know what it's like to keep these experiences hidden and to navigate school, work, and a personal life that can be unforgiving. My sister, unlike me, has an apparent disability. Students threw pencils at her and called her the "R" word. She would sob to me after school about this. As an adult with intellectual disability, she now faces the burden of a society that provides no options and appears to not value her life. It hasn't been easy, but I have channeled the intensity of my convictions to advocate for those who know why the changes we seek can mean life or death. Having a disability can be a deeply individual experience and feel incredibly isolating. As someone with a non-apparent disability, I have felt lonely for much of my life. No one could possibly understand, I thought. But, it simply wasn't true. While no two people are exactly alike, I've found that everywhere I have shared my story, people can relate. From the halls of Capitol Hill to UCLA Law school, and even in Peru, where I lived for two years, I always created connections with people who shared my experience. I've learned that if we want community, we need to consciously build it. This isn't an easy task, and it isn't going to happen over night, but it is so worth it. Everywhere you look in history, Disabled people have been organizing and fighting to be treated with dignity. Our work is an extension of this. As Latinxs, we face multiple barriers. The intersectional approach to our coalition acknowledges that systems of oppression often work together. Just as ableism and racism are intertwined, we seek to builds bridges between Latinx and Disability advocacy organizations and efforts. This type of intersectional work is what will sustain our respective rights movements. My family immigrated from Mexico to California starting in the 1940s. My grandmother, who is originally from Zacatecas, instilled the drive for education and becoming mujeres poderosas in our family. I'm reminded that she always told me to be proud to speak up and celebrate my achievements because she had learned that no one else was going to do it for her. She is a trailblazer who didn't let anyone hold her back even when they told her she couldn't teach English or become a principal because she had a heavy accent. She did both. Although my anxiety rears its ugly head telling me not to put myself out there for scrutiny, I do so because sharing my story is important. It's important that we all have the courage to share our stories. Because if we don't share our stories, our stories get erased. We must do so especially when society tells us that our lives are unworthy. And while we are celebrating the good, we must also call out the bad. I have had the great privilege to work with an incredible group of Disabled Latinxs and allies over the last several months in creating the National Coalition for Latinxs with Disabilities (CNLD). Any praise that I receive for CNLD is praise for a shared effort. And on behalf of our group, I urge all of you who know what it's like to feel like "a little weird and out of place" (and those who are allies) to join us in solidarity! I promise you that I will continue to work my hardest as one of the leaders in this movement. AAPD Paul G. Hearne Leadership Award Recipient Announcement |

Authors.Members of CNLD regularly write posts, though we accept posts from our audience! Archives

January 2019

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed